Horatio, Back in Wittenberg

Nicholas B. Morris

1

Fortinbras was, of course, the first to hear the tale of Hamlet, the tragic prince of Denmark. The new king had listened with an attentive ear, and allowed Horatio to remain at Elsinore until he felt he had served his grief well. After he had performed the eulogy and cried into Hamlet’s grave, after he had borne witness to the elegant coronation of Fortinbras as the latest ruler of Denmark, after he had secured the promise of safe passage from the new king, Horatio gathered up his meager collection of books and started the long journey back to Wittenberg.

He spent much of the trip staring into space, seeing but not noticing the scenery. The sun remained clad in a mantle of dark clouds; Horatio wondered if he might ever feel its rays on his face again.

2

Back in Wittenberg, his friends tried to cheer him up. They took him to the beer halls, got the dancing girls to flirt with him, engaged in the spirited philosophical debates he had so enjoyed before the trip to Denmark. But nothing could quite shake off the melancholy that loomed above his head at all times.

He arrived only a few days into the new term, so he buried himself in his studies in the hopes of forgetting his grief. His professors generously gave him ample opportunities to make up late work, and his fellow students offered their support as well. Still, Horatio didn’t feel the same passion for scholarship anymore. He spoke to the headmaster and requested a leave of absence. The gentleman told Horatio to take his fair leave and return when he felt ready.

3

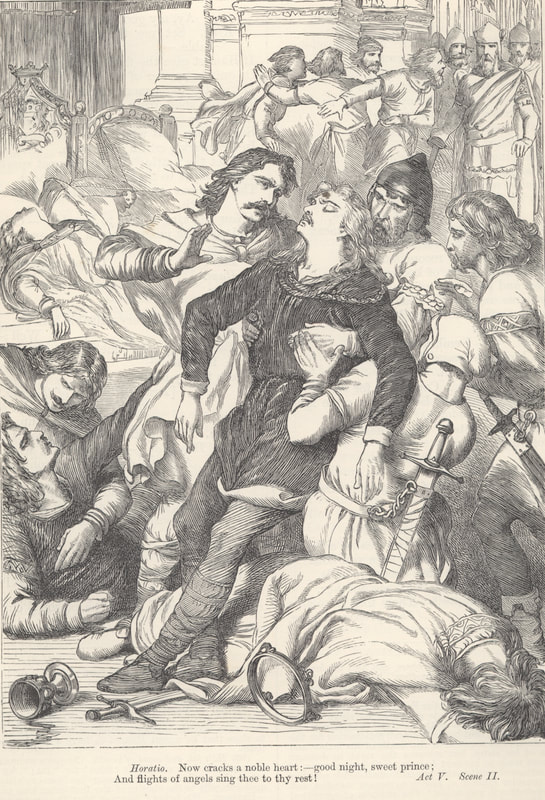

Horatio wandered the streets of Wittenberg, trying to figure out why he felt so lost without Hamlet. He recalled the good times over many beers, the lively intellectual conversations, the many jokes that Hamlet had told, at which he’d laughed until his sides hurt. He had barely kept up with the quick-witted humor of the brilliant, if troubled, young prince of Denmark. A smile curled at his lips for a moment before he remembered his beloved friend, almost a brother, wrecked with depression at the loss of his father; the mad glint in his eye after “The Mousetrap” at Elsinore; the lines of pain on his brow when he saw Ophelia laid in the cold ground. He remembered the resolve with which Hamlet had accepted the wager to fence with Laertes, the powerful dying fingers that had pried loose the poisoned chalice from his own hand (now gripping a near-empty stein), the grim resignation in his voice as he’d announced that the rest was silence.

Before he knew it, he found himself telling Hamlet’s story again, and like many times before, the barkeep asked him, not unkindly, to leave.

4

For many weeks, Horatio contemplated suicide. He knew it would damn him–self-slaughter is a mortal sin–but he found that he couldn’t shake the thought. He kept playing Hamlet’s musings on the subject over and over in his mind, and wondered if his friend had decided on the proper course. He discussed the matter with his pastor and his mentor at the university, but found the answers both men gave unsatisfactory. He even visited the closest Catholic priest, some twenty miles away, just to see if Catholic doctrine treated suicides any kinder, but he found no relief.

With only Hell to look forward to, Horatio tried to find joy in the everyday world. The bird’s songs did not help; they reminded him too much of the sweet chirping Ophelia had done in the throne room as she raved in her insanity. Theater was out of the question; Hamlet had so loved the dramatic arts. Literature brought him little joy, and prayer even less. His friends had long since ceased to ask him to drinks; the clouds that rained down on the drunken, weeping Horatio flooded everyone around him. The last time he had gone for beers, his friends had confiscated Horatio’s dagger to keep him from harming himself, and since then, no one had even bothered asking him to join them.

Instead, he stayed in his flat, telling the same story again and again, hoping each time that he would figure out where everything went wrong, what he might have done to stop the bloodshed. But the ultimate meaning of Hamlet’s story eluded him, always raising more questions, and answering fewer of them with each retelling.

Nicholas B. Morris

1

Fortinbras was, of course, the first to hear the tale of Hamlet, the tragic prince of Denmark. The new king had listened with an attentive ear, and allowed Horatio to remain at Elsinore until he felt he had served his grief well. After he had performed the eulogy and cried into Hamlet’s grave, after he had borne witness to the elegant coronation of Fortinbras as the latest ruler of Denmark, after he had secured the promise of safe passage from the new king, Horatio gathered up his meager collection of books and started the long journey back to Wittenberg.

He spent much of the trip staring into space, seeing but not noticing the scenery. The sun remained clad in a mantle of dark clouds; Horatio wondered if he might ever feel its rays on his face again.

2

Back in Wittenberg, his friends tried to cheer him up. They took him to the beer halls, got the dancing girls to flirt with him, engaged in the spirited philosophical debates he had so enjoyed before the trip to Denmark. But nothing could quite shake off the melancholy that loomed above his head at all times.

He arrived only a few days into the new term, so he buried himself in his studies in the hopes of forgetting his grief. His professors generously gave him ample opportunities to make up late work, and his fellow students offered their support as well. Still, Horatio didn’t feel the same passion for scholarship anymore. He spoke to the headmaster and requested a leave of absence. The gentleman told Horatio to take his fair leave and return when he felt ready.

3

Horatio wandered the streets of Wittenberg, trying to figure out why he felt so lost without Hamlet. He recalled the good times over many beers, the lively intellectual conversations, the many jokes that Hamlet had told, at which he’d laughed until his sides hurt. He had barely kept up with the quick-witted humor of the brilliant, if troubled, young prince of Denmark. A smile curled at his lips for a moment before he remembered his beloved friend, almost a brother, wrecked with depression at the loss of his father; the mad glint in his eye after “The Mousetrap” at Elsinore; the lines of pain on his brow when he saw Ophelia laid in the cold ground. He remembered the resolve with which Hamlet had accepted the wager to fence with Laertes, the powerful dying fingers that had pried loose the poisoned chalice from his own hand (now gripping a near-empty stein), the grim resignation in his voice as he’d announced that the rest was silence.

Before he knew it, he found himself telling Hamlet’s story again, and like many times before, the barkeep asked him, not unkindly, to leave.

4

For many weeks, Horatio contemplated suicide. He knew it would damn him–self-slaughter is a mortal sin–but he found that he couldn’t shake the thought. He kept playing Hamlet’s musings on the subject over and over in his mind, and wondered if his friend had decided on the proper course. He discussed the matter with his pastor and his mentor at the university, but found the answers both men gave unsatisfactory. He even visited the closest Catholic priest, some twenty miles away, just to see if Catholic doctrine treated suicides any kinder, but he found no relief.

With only Hell to look forward to, Horatio tried to find joy in the everyday world. The bird’s songs did not help; they reminded him too much of the sweet chirping Ophelia had done in the throne room as she raved in her insanity. Theater was out of the question; Hamlet had so loved the dramatic arts. Literature brought him little joy, and prayer even less. His friends had long since ceased to ask him to drinks; the clouds that rained down on the drunken, weeping Horatio flooded everyone around him. The last time he had gone for beers, his friends had confiscated Horatio’s dagger to keep him from harming himself, and since then, no one had even bothered asking him to join them.

Instead, he stayed in his flat, telling the same story again and again, hoping each time that he would figure out where everything went wrong, what he might have done to stop the bloodshed. But the ultimate meaning of Hamlet’s story eluded him, always raising more questions, and answering fewer of them with each retelling.