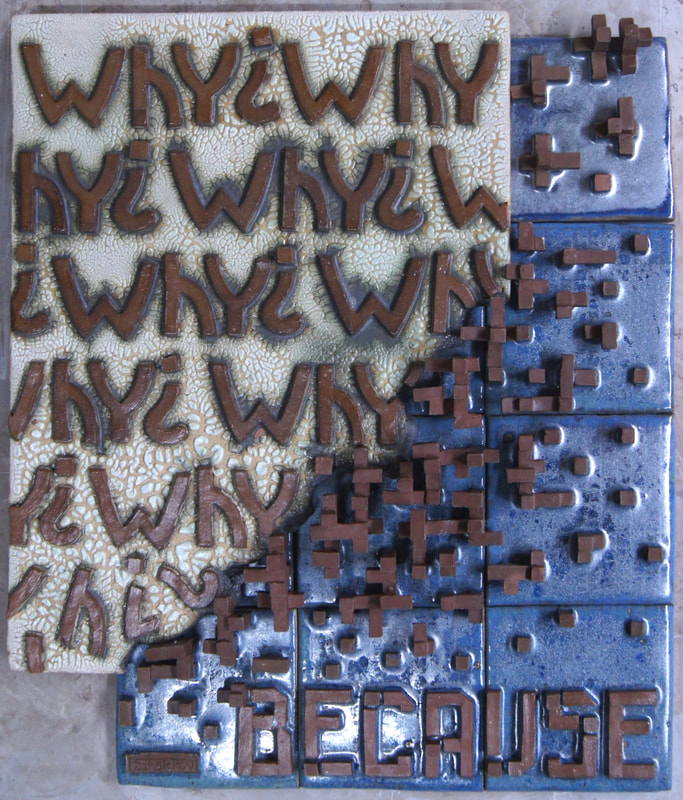

Second Original, or, On Repetition

Jomil Ebro

When I heard hyperventilating my old body

in the bathtub, under ferried fog and a jury of candles,

I opened the door so he could catch his breath.

He was all talk of fire back then: of repetitions of light,

of invincible summers in the depths of winter.

He was good at answers–sure, but not at living the questions yet.

Now, squatting in the cold water like a belated miner, I told him,

Before you become gold, can you listen to the ore?

Before you heal, are you willing to give up the things that made you sick?

With nothing but faith, nothing but poor translation, I told him.

How can you revise the ending of the same story?

T-boned by aloneness–how do we endure such a dent?

One road is untrodden, the other is slant.

I had to tell myself a new story so that I could find you–a new reader.

To write at all, or again–to surrender to re-vision–is its own forlorn and holy

Pulitzer, an unbearably light prize for choosing a new name: kingdom come,

sigh and will be done on earth as it is in heavy things.

I had to forge the ore of grief, repeat hammerings, for length changes depth.

I had to choose beyond the demands of survival, of children, of the past.

To decipher the language of one’s soul and hear it in another

is to enhearth a new marriage, to resurrect two pillars that are not one,

but not two either–something greater than themselves: lips to a temple,

ringed with pineapple Chapstick (the only gold bands we can afford).

In the sea of naked novas, the brute black world, love has no real flesh nor wind.

Yet in the plungeless dark, how fiercely my body is appendaged by yours:

nocturnal octopus of audacity.

Whatever a correct translation is of a second chance–

of the will to up and encore yourself out of the house–

fumbling it is the evidence of life. This heaving ribcage of a life.

What words can do justice to the millioned-morsel of starlings?

To that pointillist composer scoring the open-air wound of this world?

To the way we hang on,

the way we can wing close to another but not collide?

Yet, our world has reified the rubble: skyward mortuaries

Morse Code the ground and make the most efficient graves

upon a people for whom it is illegal to collect rainwater.

There are oranges oranges oranges all over the ground,

caughtless, commaless.

So the starlings, those shimmering gold flakes,

have not risen in a long time.

They look at what humans have written: language walls, gored plosives,

evicted vowels, 1s and 0s, either/ors.

They can’t quilt the air without an ether porous;

they’re shuddering as we perfect genocide and automation.

With nothing hopeful to mimic, they have forgotten how to soar.

“Nothing gold can stay,” Frost warned us at sunset.

Those birds of noir long to stain again the mouth of the sky like vanilla drops.

Unmoored by the A.I.’ed, unalive stories that dried the humid calligraphy

of the heart, the starlings harpooned into hiding.

They do that when nourishment is scarce.

But in the mutter of the silver maple, I heard them ask,

“Could anyone write something real and beautiful and original

so that we may be unorphaned from our home?”

My answer to the question is too battered to be beautiful,

but it is a translation that is my own, stammering like an uneven orchard,

but with sudden fruit I rustle to caress, only to notice I am caressing:

All that I love tonight—your legs whorled around mine, the sharp smells of brandy

and leftover apple crumble fencing in the air,

the blood-clot of the hibiscus spattering from the shorn tree of time–

might be lost tomorrow. So reinterpreting this life,

this life in which we prepare children by writing their names on their limbs–

little arms that are slow to fly a kite and quick to be blazed–

this same life in which the archaeology of your breathfugue

oxidizes and reveals an inborn treasure; re-envisioning this shimmering, shimmering life

is all I can ever do. This is all we ever do: repaper a tattered life.

And still, it is not quite the job of poetry to catch the breath.

Poetry ought to hollow out a planet in your throat–

(carving a mercy adorned in silence) –so that you can exhale a universe.

So that little by little, tremoring rib by tremoring rib,

what you say upon re-choosing the world is a translation

that stops being a translation and becomes s,

a second original. n g

r l i

You will say in good faith, Ah, this is an old story. And I will say to the rising s t a

to you: No, trust me: you’ve never seen this before.

In the tub, I watch the bathwater drain in golden ratios as if for the first time, singing.

Sitting stranded in this cold kayak, here I am, repeated.

I am ready to give you the topography of my eyes

so that you can run your thumbs across them,

forehead on forehead, and murmur, “Which borders are safe to cross?”

And I can answer, “Everywhere, now. Everywhere, now.”

Some things stay.

Jomil Ebro

When I heard hyperventilating my old body

in the bathtub, under ferried fog and a jury of candles,

I opened the door so he could catch his breath.

He was all talk of fire back then: of repetitions of light,

of invincible summers in the depths of winter.

He was good at answers–sure, but not at living the questions yet.

Now, squatting in the cold water like a belated miner, I told him,

Before you become gold, can you listen to the ore?

Before you heal, are you willing to give up the things that made you sick?

With nothing but faith, nothing but poor translation, I told him.

How can you revise the ending of the same story?

T-boned by aloneness–how do we endure such a dent?

One road is untrodden, the other is slant.

I had to tell myself a new story so that I could find you–a new reader.

To write at all, or again–to surrender to re-vision–is its own forlorn and holy

Pulitzer, an unbearably light prize for choosing a new name: kingdom come,

sigh and will be done on earth as it is in heavy things.

I had to forge the ore of grief, repeat hammerings, for length changes depth.

I had to choose beyond the demands of survival, of children, of the past.

To decipher the language of one’s soul and hear it in another

is to enhearth a new marriage, to resurrect two pillars that are not one,

but not two either–something greater than themselves: lips to a temple,

ringed with pineapple Chapstick (the only gold bands we can afford).

In the sea of naked novas, the brute black world, love has no real flesh nor wind.

Yet in the plungeless dark, how fiercely my body is appendaged by yours:

nocturnal octopus of audacity.

Whatever a correct translation is of a second chance–

of the will to up and encore yourself out of the house–

fumbling it is the evidence of life. This heaving ribcage of a life.

What words can do justice to the millioned-morsel of starlings?

To that pointillist composer scoring the open-air wound of this world?

To the way we hang on,

the way we can wing close to another but not collide?

Yet, our world has reified the rubble: skyward mortuaries

Morse Code the ground and make the most efficient graves

upon a people for whom it is illegal to collect rainwater.

There are oranges oranges oranges all over the ground,

caughtless, commaless.

So the starlings, those shimmering gold flakes,

have not risen in a long time.

They look at what humans have written: language walls, gored plosives,

evicted vowels, 1s and 0s, either/ors.

They can’t quilt the air without an ether porous;

they’re shuddering as we perfect genocide and automation.

With nothing hopeful to mimic, they have forgotten how to soar.

“Nothing gold can stay,” Frost warned us at sunset.

Those birds of noir long to stain again the mouth of the sky like vanilla drops.

Unmoored by the A.I.’ed, unalive stories that dried the humid calligraphy

of the heart, the starlings harpooned into hiding.

They do that when nourishment is scarce.

But in the mutter of the silver maple, I heard them ask,

“Could anyone write something real and beautiful and original

so that we may be unorphaned from our home?”

My answer to the question is too battered to be beautiful,

but it is a translation that is my own, stammering like an uneven orchard,

but with sudden fruit I rustle to caress, only to notice I am caressing:

All that I love tonight—your legs whorled around mine, the sharp smells of brandy

and leftover apple crumble fencing in the air,

the blood-clot of the hibiscus spattering from the shorn tree of time–

might be lost tomorrow. So reinterpreting this life,

this life in which we prepare children by writing their names on their limbs–

little arms that are slow to fly a kite and quick to be blazed–

this same life in which the archaeology of your breathfugue

oxidizes and reveals an inborn treasure; re-envisioning this shimmering, shimmering life

is all I can ever do. This is all we ever do: repaper a tattered life.

And still, it is not quite the job of poetry to catch the breath.

Poetry ought to hollow out a planet in your throat–

(carving a mercy adorned in silence) –so that you can exhale a universe.

So that little by little, tremoring rib by tremoring rib,

what you say upon re-choosing the world is a translation

that stops being a translation and becomes s,

a second original. n g

r l i

You will say in good faith, Ah, this is an old story. And I will say to the rising s t a

to you: No, trust me: you’ve never seen this before.

In the tub, I watch the bathwater drain in golden ratios as if for the first time, singing.

Sitting stranded in this cold kayak, here I am, repeated.

I am ready to give you the topography of my eyes

so that you can run your thumbs across them,

forehead on forehead, and murmur, “Which borders are safe to cross?”

And I can answer, “Everywhere, now. Everywhere, now.”

Some things stay.