Seeds

Jude Brigley

I have always been interested in genealogy and love the television program Who Do You Think You Are?where celebrities delve into their past generations. Neither being famous enough or interesting enough to have a television program based on my family’s history, I decided to give myself the program’s treatment. I already knew a great deal about my immediate family circle, so I delved with the help of the Internet further back. Imagine my surprise to find myself tenuously linked with Lady Margaret Whitehorse Capet (Squire) Moore, the rumored issue of Louis de Bourbon, bishop of Liège, through the Adams line. Even more surprising was to find that my fifteenth great-grandmother was none other than Bessie Blount, the mistress of Henry VIII and mother of Henry Fitzroy. I could trace her through her son George Tailboys. Not all relatives were so much fun. I was not sure I wanted to be associated with a crusader like John de Mowbray, my nineteenth great-grandfather, who was slain near Constantinople, or the dreadful Lord Ralph Eure, my thirteenth great-grandfather, who died at the Battle of Ancrum Moor in 1545, rightly hated by the Scots for his pillaging and for burning Brumehous Tower with the lady and her children inside. The Earl of Arran described him as a fell cruel man and over cruel, which many a man and fatherless bairn might rue, and wellaway that ever such slaughter and bloodshedding should be amongst Christian men. Amen to that. Happier was knowing that my eleventh great-grandmother, Joan Fisher, married the poet Thomas Wyatt’s grandson. It was her second marriage, so not a direct link, but as a long-time fan of Wyatt’s poetry (For when this song is sung and past, / My lute be still, for I have done), it will do. Imagine what the television program would make of all this if only I were famous.

After a while, I realized an obvious point–it is only if you have money and power that your ancestors are so easily accessible. My Welsh and Irish families were not so easy to trace beyond the seventeenth century. And in the past women and second sons did not inherit title or land. Hundreds if not thousands of people can trace their beginnings to such families. It reminded me of Tess of the d’Urbervilles, when Mr. Durbeyfield speaks to the vicar:

“And where be our family mansions and estates?”

“You haven’t any.”

“Oh? No lands neither?”

“None; though you once had ’em in abundance, as I said, for your family consisted of numerous branches. In this county there was a seat of yours at Kingsbere, and another at Sherton, and another in Millpond, and another at Lullstead, and another at Wellbridge.”

“And shall we ever come into our own again?”

“Ah–that I can’t tell!”

“And what had I better do about it, sir?” asked Durbeyfield, after a pause.

“Oh–nothing, nothing; except chasten yourself with the thought of ‘how are the mighty fallen.’ It is a fact of some interest to the local historian and genealogist, nothing more.”

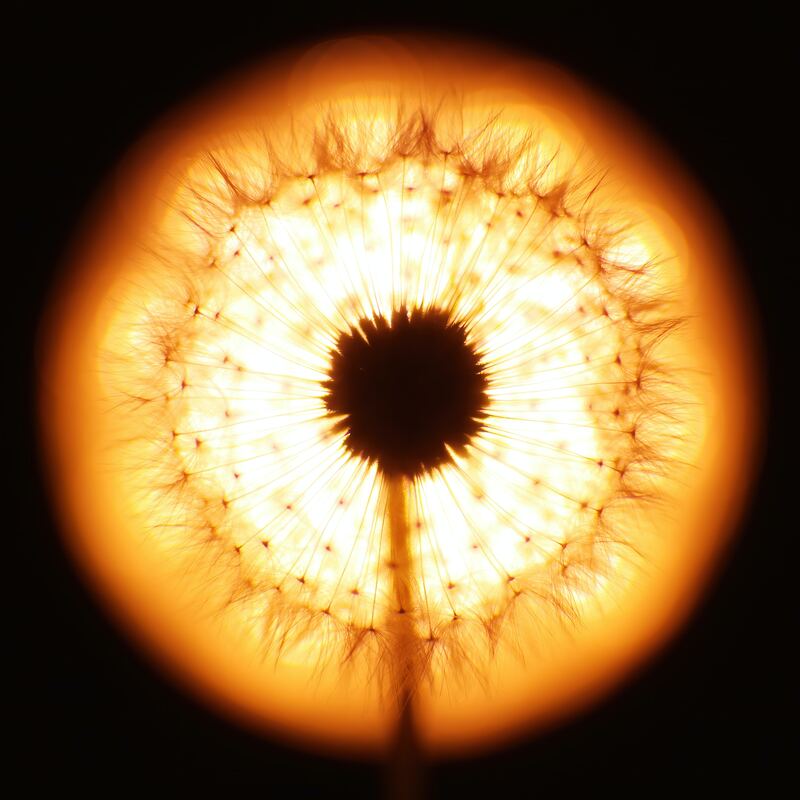

A few days ago, the fields beyond my house were glowing with golden dandelions, whose name is derived from the fourteenth-century translation of Latin, not, disappointingly, from the French, who point out the diuretic properties of the plant in their word, pissenlits, and not the jagged leaves of the plant. Earlier, I was walking in the same fields, when I noticed that it was positively throbbing with dandelion puffballs. The breeze shook them; they were dispersing. Those seeds, I know, can travel for five miles or more on a breeze or the wing of a bird. There was a gathering of the globes, and each head contained large clusters of individuals. There seemed something cosmic in their splendour, hundreds of round moons dispensing their stars to the elements. A litter of dandelion seed heads. It made me think.

Jude Brigley

I have always been interested in genealogy and love the television program Who Do You Think You Are?where celebrities delve into their past generations. Neither being famous enough or interesting enough to have a television program based on my family’s history, I decided to give myself the program’s treatment. I already knew a great deal about my immediate family circle, so I delved with the help of the Internet further back. Imagine my surprise to find myself tenuously linked with Lady Margaret Whitehorse Capet (Squire) Moore, the rumored issue of Louis de Bourbon, bishop of Liège, through the Adams line. Even more surprising was to find that my fifteenth great-grandmother was none other than Bessie Blount, the mistress of Henry VIII and mother of Henry Fitzroy. I could trace her through her son George Tailboys. Not all relatives were so much fun. I was not sure I wanted to be associated with a crusader like John de Mowbray, my nineteenth great-grandfather, who was slain near Constantinople, or the dreadful Lord Ralph Eure, my thirteenth great-grandfather, who died at the Battle of Ancrum Moor in 1545, rightly hated by the Scots for his pillaging and for burning Brumehous Tower with the lady and her children inside. The Earl of Arran described him as a fell cruel man and over cruel, which many a man and fatherless bairn might rue, and wellaway that ever such slaughter and bloodshedding should be amongst Christian men. Amen to that. Happier was knowing that my eleventh great-grandmother, Joan Fisher, married the poet Thomas Wyatt’s grandson. It was her second marriage, so not a direct link, but as a long-time fan of Wyatt’s poetry (For when this song is sung and past, / My lute be still, for I have done), it will do. Imagine what the television program would make of all this if only I were famous.

After a while, I realized an obvious point–it is only if you have money and power that your ancestors are so easily accessible. My Welsh and Irish families were not so easy to trace beyond the seventeenth century. And in the past women and second sons did not inherit title or land. Hundreds if not thousands of people can trace their beginnings to such families. It reminded me of Tess of the d’Urbervilles, when Mr. Durbeyfield speaks to the vicar:

“And where be our family mansions and estates?”

“You haven’t any.”

“Oh? No lands neither?”

“None; though you once had ’em in abundance, as I said, for your family consisted of numerous branches. In this county there was a seat of yours at Kingsbere, and another at Sherton, and another in Millpond, and another at Lullstead, and another at Wellbridge.”

“And shall we ever come into our own again?”

“Ah–that I can’t tell!”

“And what had I better do about it, sir?” asked Durbeyfield, after a pause.

“Oh–nothing, nothing; except chasten yourself with the thought of ‘how are the mighty fallen.’ It is a fact of some interest to the local historian and genealogist, nothing more.”

A few days ago, the fields beyond my house were glowing with golden dandelions, whose name is derived from the fourteenth-century translation of Latin, not, disappointingly, from the French, who point out the diuretic properties of the plant in their word, pissenlits, and not the jagged leaves of the plant. Earlier, I was walking in the same fields, when I noticed that it was positively throbbing with dandelion puffballs. The breeze shook them; they were dispersing. Those seeds, I know, can travel for five miles or more on a breeze or the wing of a bird. There was a gathering of the globes, and each head contained large clusters of individuals. There seemed something cosmic in their splendour, hundreds of round moons dispensing their stars to the elements. A litter of dandelion seed heads. It made me think.